Political maneuverings, influenced by special interests that benefit from rapid growth, continue to plague Florida with ineffectual policies on water. It should be clear at this point that a significant new course of action is necessary to avoid the outcomes of entrenched politics with a stricter interpretation of the law by the courts.

The failed outcomes of past water policy interpretation, based on concepts of reasonable assurance or reasonable and beneficial use by the Florida legislature and thus the state agencies responsible for compliance and enforcement over past decades, make a strong case that a new approach is necessary.

As recently as 2003, Florida agencies interpreted state rules about adequate water to sustain natural systems that are supposed to be set aside “off the top”, without requiring a permit or reservation to ensure that natural systems will be protected from water overallocation.

The fallacy of that interpretation was made evident by the SFWMD’s 2008 Lake Okeechobee Water Availability Rule sometimes referred to as the “No Farmer Left Behind” policy that entitled farmers to public water based on any history of past use. The end result was a larger allocation to agriculture ensuring use by permit for up to 30 years.

Regional water supply plans in South Florida continue to document the increasing demand for water, a finite resource, for both domestic and agricultural uses.

Again, the concern has to do with balancing state and federal interpretation of water law or other requirements of regulation to sustain natural waters. Existing Florida policy related to minimum flows and levels going back to the 1990s, allowed for a statutory “reservation” of existing water to assure the needs of the natural system but the state did not have the political will to adopt water reservations. Often, the excuse was uncertainty about what defines a healthy ecosystem.

Subsequently, state and federal authorities determined, as an example in Southwest Florida, that the only recovery plan for the Caloosahatchee estuary was to build the C-43 storage reservoir at a cost of a billion dollars rather than limit allocations. The reservoir, unfortunately, might only provide enough water to prevent significant harm rather than restoration.

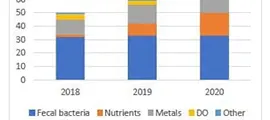

The same pattern is evident with regard to policy on water quality. A case in point is Lake Okeechobee where compliance with a state restoration program to reduce phosphorus pollution has failed to stem the increasing trend of excess loading over the past 19 years. Florida SB 552 in 2016 extended the deadline for compliance on that plan, once again, many years into the future.

The failure to reign in polluted agricultural runoff from farms in the Lake Okeechobee watershed on the basis that Agricultural Best Management Practices are effective, remains an ongoing problem. Similarly, state policies aimed at reducing pollutants in stormwater runoff from urban areas have failed miserably. The cumulative result is widespread toxic algae blooms and impairment of Florida’s waters.

Attempts to redirect Florida water policy by a citizen petition such as the 2014 Florida Water and Land Conservation Initiative, have not lived up to the citizens’ intent of the constitutional amendment to conserve water and land.

The pattern is clear, Florida will not untether itself from the influence of special interests to prevent further decline of its waters. Florida’s SB 712, which preempts a new basis for water law like Orange County’s “Right to Clean Water” initiative is further evidence.

Other Florida communities should follow Orange County’s lead toward an urgent new approach for conserving Florida’s waters.