The Sunshine State added almost 3 million people in the past 10 years, swelling from 18.8 to 21.7 million and muscling into the No. 3 spot in the nation, pushing New York down to No. 4. Only California and Texas topped it, with 39.3 million and 29.3 million respectively.

So where did all those newcomers go?

Predictably, much of the increase hugged the coasts, but inland hotspots surged as well. Retirement haven The Villages in central Florida’s Sumter and Lake counties grew by 39%, a rate that was higher than any other metro area in the nation, while nearby Orange County (with attraction-rich Orlando) rose 21.6% to 1.4 million.

That burgeoning growth raises questions about how the state’s wildlife, wetlands and water resources will fare in the more crowded future.

All those newcomers mean more cars, homes, lawns, toilet flushes and garbage. It also means less agricultural land, fewer trees, more pressure on springs and groundwater, increased runoff from roads and discharges into rivers and bays. New communities and wider roads criss-cross living space for black bears, gopher tortoises and the endangered Florida panther. Heavier boat traffic means more danger for manatees.

It behooves the state to grow carefully, balancing newcomers’ needs with those of the natural systems. “We are seeing how inextricably tied our economy is to our environment,” said Meredith Budd, regional policy director of the Florida Wildlife Federation, a statewide conservation-focused nonprofit, “and we need a very forward thinking population and leadership in that way, and we need more actual steps toward that goal, but step one is acknowledging that we need to do better.”

Since the state’s growth happens regionally, discussions and planning should be regional as well, she says.

“Working in silos in each independent municipality or county doesn’t function to reach that goal of regionalism,” Budd said. “Government agencies need to be at the same table as landowners, as (nonprofits) that are bringing technical expertise (and) planning experts – even from transportation departments, because when you talk about development, that means roads as well.”

Just as important as protecting land, Budd says, is ensuring that road placement is done properly “So that wildlife resources and water resources are considered at the onset of planning,” she said.

Bottom line: “We need a state planning agency.”

Roads to Extinction?

Earlier this year, many Florida environmental advocates breathed a sigh of relief when plans for three controversial toll roads were shelved.

Originally, the 2019 Multi-use Corridors of Regional Economic Significance (M-CORES) legislation would have meant 300-plus miles of new roads built across some of the state’s most fragile environments.

In June, however, Senate Transportation Committee Chair Gayle Harrell (R-Stuart), essentially repealed it.

The near-miss was a wake-up call, said South Florida Wildlands Association Executive Director Matthew Schwartz, pointing up the need for lawmakers and the public to be better educated about the causes and effects of sprawl.

“New roads are never standalone in Florida,” said Schwartz. “It’s not like we ever have a road that goes in by itself – it’s always in response or in anticipation of new development,” he said. “Roads and growth go hand in hand.”

Had the three new corridors gone in, Schwartz said, “an explosion of growth all around” would have resulted. “And that’s where the main habitat loss comes from.”

That’s not to say road projects can’t be designed to be more compatible with wildlife needs, he says, “The way they built I-75 Alligator Alley across the Big Cypress, and they put lots of underpasses in there and the wildlife all uses it. The difference there is you’ve got wild lands on both sides, so they’re moving from one part of the preserve to the other and it’s connected.”

M-CORES wouldn’t have done that.

“When you put in a road and it gets developed alongside, that’s no longer the case. Now you’ve got a road, development, access roads coming in and out. You can’t fence it off so it’s a whole cascade of impacts.”

When Audubon Florida Director Julie Wraithmell was growing up in Central Florida there were just 10 million people in the state, yet today’s discussions – or lack thereof – often remind her of those times.

“We continue to make land-use decisions that act as though we’re still a 10 million-person state sometimes,” she said.

Unfortunately, such decisions add up, Wraithmell says. “They’re’ cumulative.”

And unchecked, they lead to sprawl, a generally reviled outcome, says Schwartz.

“If you talk to rank and file people and you ask them what do you dislike most about living in Florida in 2021, they’ll say development. Everybody hates sprawl.”

It reminds him, he says, of one of Yogi Berra’s famous lines: “Oh, nobody goes there any more – it’s too crowded.”

Same is true of this place, he says. “This level of development, nobody likes it (and) people see it’s nonstop and they get nothing out of it.

“And now, the state of Florida in the last legislative session changed the laws affecting impact fees, so all this new growth is no longer able to charge the full price to the developers,” Schwartz said. “which means the cost of the new roads, the hospitals, the sewer systems are going to be transferred to the existing residents. So if I’m a resident seeing all this sprawl all around me, I’m going to get nothing out of it. People are going to get upset.”

“I would say we’ve reached carrying capacity,” he said. “If we want to maintain wildlife and the quality of our public lands, then we need to draw a line.”

Another Southwest Florida Boom

Over the last decade, Lee and Collier counties, on the peninsula’s southwestern corner, rose to 1.1 million souls, adding about 200,000 people in the just the past 10 years.

Collier’s population of 376,000 is a 17% jump in the 10 years, while Lee’s 761,000 is up by 23%. By way of comparison, their combined 1970 population was 109,000. If someone said then there would be 10 times more people in the area by 2020, they would have been quite right.

The growth comes at a time when the state has pulled nearly all the power from its regional planning councils, which used to help shape multi-area growth patterns until Gov. Rick Scott moved to dismantle that approach. Now, how growth is – or isn’t – planned depends on local governments with input from advocates, businesses and citizens.

For example, every year Collier creates an Annual Update and Inventory Report, “the plans for all our infrastructure providers over the next five to 10 years,” said Planning and Zoning Division Director Mike Bosi. “It’s designed to be able to maintain the levels of service in the expansion of the needed infrastructure to handle the additional population that we expect over those five- and 10-year periods.”

The counties are wrestling with “tremendous growth and development pressure throughout Southwest Florida, especially in Lee and Collier counties,” said Florida Wildlife Federation’s Budd.

“Local governments can always take a more proactive approach to those protections. That’s something we’ve promoted and advocated for,” Budd said. “It’s incredibly important that we strike a proper balance.”

Saving Some of What’s Left

Meanwhile, both Lee and Collier have shouldered responsibility for planning the way the counties set aside land for preservation.

Since 1996, with taxpayer blessings, Lee County’s Conservation 20/20 has enabled Lee County to buy and manage property essential for wildlife habitat, water supply, flood protection and recreation.

The county’s comprehensive plan says the ultimate goal is to have 62,000 acres in conservation land. The county is about halfway to the goal with more than 30,000 acres preserved so far in the program.

To the south, the popular Conservation Collier Program, which voters recently approved with a 77% vote, holds 4,345 acres in 21 different locations, and the county also is home to the 729,000-acre federal Big Cypress National Preserve.

All those newcomers need places to live, and in Collier, housing for a growing population is pushing eastward, away from the coast. A recent spate of proposed developments in the county’s environmentally sensitive Rural Land Stewardship Area sparked a fight over smart growth, and how to accommodate the influx of new residents in a way that protects vital habitats.

Nicole Johnson, director of environmental policy at the Conservancy of Southwest Florida, said one of the things the group is seeing is that Southwest Florida is moving away from the second-home, retirement community landscape.

“What we are hoping to see and haven’t really seen yet is the building development community responding by creating a difference in the products they make,” Johnson said. “What we’re finding is that not everyone wants to live in gated, golf course community.”

Younger people want walkability, she said, such as communities where it’s not necessary to rely on a car to grab a bite to eat or get a haircut. Not only should new communities be built with walkability, but Johnson said the Conservancy encourages redevelopment.

“Redevelopment is one of the areas where you can take an old shopping center that isn’t being maximized to create residential units on top of businesses,” she said. “Areas like Mercato or 5th Avenue, but with affordability.”

Both counties are setting aside preserve land, but advocates worry it’ll be too little, too late. Chipping away at open space, at habitat areas, at vegetated areas does not bode well for the future of Collier’s greenspace, Johnson says. There are a lot of opportunities for redevelopment if there is going to be continued expansions, she said. It’s about developing in the right location.

While considering a growing number of residents, Johnson said there needs to be an adherence to development regulations already on the books, especially in eastern Collier.

April Olson, senior environmental planning specialist at the Conservancy, said the villages in Collier’s Rural Lands Stewardship Area, which aims to enhance environmental and agricultural preservation, while allowing for smart growth and development. did not comply with certain rules, namely walkability, self-sufficiency and a compact design. “(The villages) are supposed to be places where people can live and work without having to leave their community or travel west,” she said.

Pitched as sister settlements, developers want to build Rivergrass, Longwater and Bellmar by swapping credits to “preserve 10,000 acres of environmental lands — at no cost to Collier County taxpayers,” the developer’s website promises.

The overarching concern for the Conservancy, Johnson said, is that as Collier diversifies its residential base, it’s important to have a mix of housing opportunities.

“And a mix of opportunities for someone who wants something other than a car-centric lifestyle,” she said. “And at this time, we’re not seeing a lot or that kind of development encouraged or happening. It’s really a lost opportunity.”

Florida Wildlife Federation’s Budd takes a pragmatic approach. “Is it everything I’d like to see for the environment out in eastern Collier County?” she asks. “No. I would love to see it remain as it is. But that’s not a reality.”

Fact is, property owners have rights, she said, and compacted development in already- scraped former farm fields is better than unchecked sprawl.

Budd’s nonprofit played a key role in creating the rural stewardship area, and she’s acutely aware of the need for balance and compromise. “In a world with no development rights, the Federation would love to see no development out there. But we don’t live in that world. So how can we make sure we’re protecting corridors for wildlife and protecting our water resources?” She asks. “Dialogue and compromise are a positive way to move forward because if you don’t have that dialogue, then you get nothing.”

There’s Only so Much Water

While counties, municipalities and sometimes communities are responsible for delivering and treating privately used water, the South Florida Water Management District is the agency that tries to makes sure there’s enough to go around.

The average Floridian uses about 87 gallons each day, according to the nonprofit National Environmental Education Foundation, but that doesn’t mean they should, says district spokesman Randy Smith. Water is a finite resource, he points out, and everyone can pitch in to conserve it.

The district’s conservation efforts have helped that along. In 2000, the average user in district’s lower west coast service area, which includes Lee and Collier, averaged 174 gallons a day drawn from permitted facilities like municipal systems. Those numbers, which are measured every five years, have dropped steadily. In 2015, the average was 126 gallons, a 28% decrease, said Mark Elsner, the district’s water supply expert.

“During the 2007/2008 drought (and recession) we saw this decrease in many areas and as indicated in the Districtwide number,” Elsner wrote in an email. “Residents were educated on irrigation practices, the value of water and we also rolled out of the water shortage restrictions with year-round landscape irrigation measures (restrictions) in place. In addition, new building is installing more efficient water fixtures,” all of which reduces demand on the finite supply.

It’s harder to measure water use in areas with private wells, because the district doesn’t keep track of those. A request for annual number of permits, which is handled by Florida’s Department of Health, was not immediately returned.

But There’s Plenty of Trash

All those residents old and new generate lots of waste in the form of kitchen garbage, empty bottles and tree trimmings. Each county has a different strategy for handling it, but what they have in common is the need to cope with more of it.

In Lee, where between some 250 to 425 tons of refuse enters what insiders call the waste stream daily, trash is burned and recyclables are sold, bringing in $2 million a year for stuff that would otherwise go in a landfill or be burned.

In 2010, Lee County took in 601,459 tons of county waste. By 2020, that was up to 1,034,080 tons.

Collier took in a total of 292,620 tons in 2010 and 376,272 in 2020, said spokeswoman Evelyn Longa, while pointing out that the counties’ solid waste programs are quite different, which can make the numbers appear to vary considerably.

Collier estimates its landfill has another 40 years of useful life, Longa says.

Lee’s should last at least another 20, keeping in mind that “innovation happens, technology changes, new sites may come online, etc.,” says spokesman Tim Engstrom.

Collier’s experience speaks to that, says Bosi. Even though planners predicted the county’s landfill would be obsolete by now, “through use of technology and innovative strategies, we have been able to extend (its) life,” he said.

“It’s difficult to project out, 40, 50 years to say, OK, what new technologies are going to be there (but) that has given us a good indication as to how technology and improved techniques in waste disposal allows us to continue to extend the useful life.”

Getting the Land Right to get the Water Right

Most environmental advocates see land preservation as key to water quality.

The Village of Estero is instructive. Its population increased by 63% to 37,000, all within the same watershed.

Lands there drain into streams, roads and ditches before flowing into the Estero River, which drains into Estero Bay and then into the Gulf of Mexico.

Estero Bay is the state’s oldest aquatic preserve. Classified an Outstanding Florida Water, it’s supposed to receive the highest level of protection the Florida Department of Environmental Protection offers. Yet water quality in the bay has steadily degraded over the past decade.

“Our best coastal waters, our Outstanding Florida Waters, are becoming impaired, and that’s a sign that something is terribly wrong,” said Calusa Waterkeeper John Cassani. “And growth is driving this.” Some 40 waterways in Florida share that designation including Wiggins Pass in Collier County, the Florida Keys and the Hillsborough River. Like Estero Bay, many of those waters are polluted.

Water quality problems have become common across much of the state in the past decade, with blue-green algae blooms and red tides raging along the Southwest coast and mass manatee deaths on the east coast.

Bad blooms have occurred in the past, like they did in the mid-90s, but many environmental advocates say such events have become more common and more dangerous to the environment and to people.

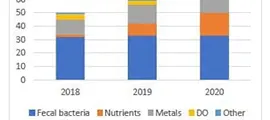

Calusa Waterkeeper earlier this year released a report focused on growth in a nine-county section of coastal Southwest Florida, and the counties with the highest growth had corresponding levels of pollutants and other water issues, Cassani said.

As of 2020, in Lee, 43% of state-identified waterbodies are polluted compared to Collier’s 24%, an increase of 36 and 25% respectively.

“We’re kind of getting to the point now where there aren’t too many options left in these highly developed basins and they’ll likely continue to contribute to the decline of waterways like Estero Bay,” Cassani said.

There are projects in play now and in the works that are designed to help.

Lee County’s John Yarborough Linear Park along 10 Mile Canal runs from Hanson Street in Fort Myers to Mullock Creek, which feeds Estero Bay. The park has become a favorite for runners, bikers, roller skaters and birdwatchers who enjoy the critters that flock to its manmade filter marsh, which helps clean water headed to the bay.

Collier County’s Gordon River Greenway functions similarly as a multi-purpose project that provides recreation for humans, habitat for wildlife and natural filtration for water quality.

But with paved, impervious surfaces increasing even faster than development, water quality will remain a challenge, Cassani says. Over the past five years, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration report showed from 2001 to 2016, Collier’s developed land increased by 14% but its impervious cover rose by almost 17%. Lee’s development went up 11% with impervious areas increasing by almost 15%.

Those hard-shelled areas areas increase how fast and how much polluted stormwater runs off the land while making it harder for that water to filter back into aquifers to recharge them for the future.

What’s Left for Wildlife?

Growth has an impact on upland areas and its non-human residents too.

Animals like the Florida panther and black bear continue to struggle to find enough habitat to thrive in what were once rural areas.

It’s not just space that’s in short supply. Even in some preserves, a major wildlife food source is disappearing as illegal palmetto berry pickers strip conservation lands clean of the fruit. They sell it to be used in medicine.

That leaves little or none for the hungry animals that eat them: protected gopher tortoises, foxes, raccoons, deer and especially black bears, who depend on them for calories. Berry theft is so prevalent a problem that Lee County tried letting a contractor take 80% of the berries in one preserve this year, and land managers at the Corkscrew Regional Ecosystem Watershed preserve are contemplating a similar move.

As their survival resources dwindle, “We’re going to have more bears showing up in people’s yards,” says longtime Collier County environmental advocate Franklin Adams. With less habitat and food, Adams says, bears turn elsewhere, often to neighborhood trash cans. “When they become a garbage bear, (the state’s wildlife agency) kills them and that’s a fact,” Adams said.

Florida panthers are under pressure as well. Of 26 total panther deaths so far this year, 20 panther were killed by vehicles, or 75%, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission reported. Of the 23 that died in all of 2010, 16 were killed by vehicles, or 69%. It’s not likely that increase is because there are more panthers, environmentalists say, but more cars.

“The loss of habitat is the leading cause of species extinction in Florida,” said Jacki Lopez, with the Center for Biological Diversity. “Florida’s growth has a big footprint and it’s a very big threat to a shifting environmental baseline.”

Lopez said many areas of the state have seen wild lands converted into mining and then into golf course communities.

“In many instances limestone mining, the future development plans, even at the limestone planning stage, have an eye toward development and it’s an industry favor to leave these industrial made lakes behind for a community,” Lopez said of developing areas like eastern Corkscrew Road in Estero near the Collier and Hendry borders.

Much of Corkscrew’s rural segment was once prime panther habitat but has, over the years, been chipped away at by development.

“It’s an erosion of that habitat,” Lopez said. “It’s sold as a benefit but at the end of the day what you’re left with is increasingly fragmented habitat.”

Even though it’s well known the area is critical for water storage, wildlife habitat and wildlife movement, “what we’re seeing is piecemeal development of individual parcels that has led to a fragmented, disconnected or tenuously connected land really having questionable function (for) wide-ranging species like our Florida panther,” Budd said. “So with the sprawl we see happening and creeping out, we really need to seek a balance.”

Since the Bert Harris Private Property Rights Act was enacted in 1995, governments have been more cautious about preservation. The Florida law essentially says government can’t burden private property owners with restrictions on how they develop their property, provided it’s a legal use.

That’s not to say it’s a blank check, Budd says.. “(We) understand there are development rights and people own private properties,” she said, so her nonprofit urges governments to offer landowners incentives “to do the right thing” while offering scientific guidance on how to go about that.

Will we East Coast the West Coast?

Historically, Southwest Florida has been seen as an alternative to the built-up Fort Lauderdale/Miami metropolis, with that side of the state serving as an example of what many residents here don’t want to become.

But that may be changing.

Adams was born in Miami, which was a great place to grow up, he says, until it got too crowded. So 51 years ago, when his children were little, he pulled up stakes and moved to Collier County.

As a land surveyor and back-country fishing guide, “I got to see a lot of beautiful places gradually destroyed,” he said: “Drained and ditched and developed.”

From those early experiences a half-century of environmental advocacy was born, with mentors including Florida conservation giants Arthur Marshall and Marjory Stoneman Douglas. What dismays Adams is the topics being discussed in the early ‘80s – growth management and water quality – are still on the table today.

“We’re still talking about the same issues and it’s the same old crap with the Legislature. We pass these things and then the Legislature doesn’t fund them or does like the (Gov. Rick) Scott administration did … just ignore it. Just so many things like that,” he said. “Somebody told me recently I’m just a grouchy old curmudgeon and maybe that’s true.”

What frustrates him is the cyclical reinvention of the environmental wheel. “We’ve already had the studies done by very educated people … that show we can avoid problems with landfills, with water, with development in the wrong places if we start to do these certain things.”

Where are those studies and all their good advice now? “On the shelf like so many others,” Adams said. “So today we’re in the mess we’re in.

“We used to say, ‘Don’t east coast the west coast.’ Well, we’re east coasting it. It’s a very valid concern. Money seems to be the prevailing thing over everything else,” he said.

Adams recalls complaining about some environmental abomination or other to a recent New Jersey transplant, “They were just looking at me like, ‘What are you talking about? I just moved down here and this place compared to where I come from looks pristine.’

“So it’s just a never-ending battle”

A key concept for policymakers and citizens, Audubon Florida’s Wraithmell says, is that conservation makes good fiscal sense. “It’s in our state’s interest to protect the environment – not just for its inherent value, but because it’s the foundation of our economy. It undergirds all of our tourism industry, our property values, and so as we add people to our state we have think about how we can do things differently so we don’t just compound some of the unsavory results we’ve experienced in the past.”

Unsavory results such as 2018’s harmful algal blooms, fed by polluted runoff from the surrounding developed land area and Lake Okeechobee, when “our economy suffered mightily,” she said. “People were walking away from multi-million-dollar real estate

transactions.

“So we need to make sure that connection is clear for people,” Wraithmell said. “We can’t keep designing a 20th-century Florida if we want a 21st-century state with the environment and good jobs for our kids and the high quality of life they deserve.”

View Article on News-Press.com