Originally published by The News-Press on February 13, 2021 by Amy Bennett Williams.

For decades, the city of Fort Myers has polluted its surrounding waters, often with raw sewage.

Now, a reckoning is at hand.

After months of investigation and negotiation with the city, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection has proposed a consent order – a legal settlement – that encompasses years of slow leaks, gushing spills, equipment failures and oversight lapses.

The agreement would either fine the city $514,450 or require it to make improvements worth $768,675, one-and-a-half times the fine. That’s the option city officials prefer, according to outgoing City Manager Saeed Kazemi.

The legal document has sparked outrage among some officials, who say it blindsided them, while it vindicates Calusa Waterkeeper, an environmental nonprofit that repeatedly warned the city about the violations contained in the order and offered help addressing them. “I was encouraged to see DEP unpack this in a way that really demonstrates the city was kind of leading us astray right from Day 1,” said Waterkeeper John Cassani.

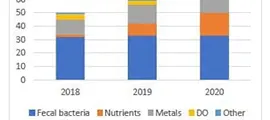

The document’s 30 pages detail a multitude of environmental sins from April 2018 through 2020, including:

- 26 raw sewage spills from its south plant, one of which “resulted in a multi-day violation of surface water quality,”

- 44 spills from its central treatment facility, including a record 183,000 gallons “with no recovery, which entered Manuel’s Branch, a tributary leading to the Caloosahatchee River”

- Chronic failure to meet state water quality standards, including the Manuel’s Branch spill and eight others.

- City treatment plants violated groundwater quality standards for arsenic and dissolved solids multiple times.

- The city repeatedly polluted the Caloosahatchee by dumping treated wastewater exceeding the permitted levels of nutrients into a part of the river “designated as a Class III water, which is meant to be suitable for recreational use and for the propagation and maintenance of a healthy, well-balanced population of fish and wildlife,” DEP notes.

- It didn’t control runoff from downtown construction sites that repeatedly sent turbid clouds of stormwater past barriers and into the river.

- The city failed to address long-term high fecal bacteria levels in Billy’s Creek and Manuel’s Branch, both Caloosahatchee tributaries. “Bacteria impairment is likely due to anthropogenic (human) causes. Respondent has not addressed or eliminated loading to water bodies of untreated human waste, which poses a risk to human health.”

It’s that last item that particularly disturbs Cassani, who’s been sounding the alarm about dangerously high bacteria in the creeks since 2001. In 2018, he wrote to then-Mayor Randy Henderson and then-Lee County Commission Chair Cecil Pendergrass urging action and offering guidance.

“We told them this has been a multi-decade problem, that something needs to be done in terms of restoration and we offered to help develop a restoration plan,” Cassani said. He got no response.

‘We’re in compliance’

Last year, Kazemi convened a water quality workshop for council members.

“During that workshop,” Cassani recalls, “the mayor said quite righteously, ‘I really wish somebody would tell Calusa Waterkeeper we’re in compliance with all these rules.’ ”

Henderson and Kazemi pointed to the city’s created filter marshes (designed to reduce sediment build-up – not fecal bacteria) and criticized Waterkeeper and media outlets that reported on its sampling. A spokeswoman said the pollution came from bird and animal poop.

That one, in particular, left Cassani scratching his head. “DEP has done (fecal bacteria) source tracing since 2018,” he said, “and I’m sorry if the city wasn’t aware of it or didn’t figure that out, but they did find human sources – a bunch of human sources (including) Sucralose,” a sugar substitute, as well as acetaminophen and human DNA.

Because mammals and birds don’t generally eat Splenda-sweetened food or take Tylenol, the presence of those chemicals in the water along with human genetic material signals a human source. “(Acetaminophen) is usually taken out with the treatment process, so if it shows up, then it’s indicating raw sewage as opposed to treated wastewater,” he said.

After the workshop, Cassani sent city officials another detailed letter with facts that contradicted their presentation but pledging collaboration on a community action plan.

The nonprofit does its own sampling, then notifies the state when it finds hot spots.

“We continued to consistently report those things to FDEP,” Cassani said, most recently about a week ago, when the nonprofit’s sampling once again showed high levels of fecal bacteria in Manuel’s Branch.

In its communications with the city, though, “We used the public record data,” Cassani said. “The only data we offered the city was what was in the state database, and they just would never accept it,” he said.

Henderson continued to publicly disparage Waterkeeper’s conclusions.

“All you hear about is the rhetoric,” he said at a meeting last year. “I worry the messaging is not in good faith and certainly not complete.”

Later in the meeting, Kazemi added, “The past six years, we’ve spent $10 million. All these filter marshes have cost money and they are doing the job,” he said. “We have done the best the city can do.”

Why didn’t the former mayor heed scientist Cassani’s warnings? He didn’t believe him, Henderson told The News-Press Thursday.

“Cassani never once reached out to me personally with any science or data that convinced me we had issues we were disregarding or (that the city was) dealing with infrastructure issues in an irresponsible way,” he said. “I wager you there’s more politics in this than facts.”

Again, Cassani is puzzled, given his multiple letters and detailed presentations to the city council. “I might even still have the PowerPoint,” Cassani said. “So yes, I personally addressed him … I think his memory is not serving him well.”

To the fact that Cassani presented officials with the same information the state collected, Henderson said, “That’s news to me. And if that’s true, why didn’t the DEP meet with Saeed and city leadership and offer guidance through the process?”

If things were so bad, Henderson wonders, why didn’t the state step in earlier? “DEP has the obligation to guide the city on such matters,” he said. “We’re a city of 130-plus years, and parts of the city have exceedingly old infrastructure.”

Though Henderson hadn’t yet read the DEP document he suggests it might well seem worse than it really is.

“The consent decree on its surface looks ugly, but it’s kind of like reading text messages …. you wonder, ‘What do they mean by that?’ ” he said. “And it’s unsettling, especially to the layperson. But they’re not going to take that $500,000 and put it in their coffers – they’re saying go fix these things.”

Rather than thinking of it “as a reprimand or report of wrongful doing,” Henderson wrote in a subsequent email, “It is an instrument of urgent improvement to remedy a menace to public safety.”

Dealing with the Threats

Henderson staunchly defends Kazemi, whose two decades of work he calls “a great deal for the citizens of Fort Myers … Saeed is among the most competent and accomplished public executives I have worked with in my professional life. In his 20 years of service, he did not achieve the many milestones to his credit by misleading or cheating the system. This is simply not reality.”

He points to plans to revise the city’s aging wastewater handling system, including “The ultimate goal of getting the infrastructure fixed so we can push (treated wastewater) across to Cape Coral and have them take our re-use water,” he said. “When we get that done, we’re out of the river for good, which has always been the goal.”

In the meantime, Henderson says breaks and glitches are to be expected.

“Until we get to at least 80 percent renewed in the infrastructure, we’re still going to have these threats, so the goal is to deal with the threats.”

That’s not good enough, says City Councilman-turned-Mayor Kevin Anderson, who blames that attitude for the city’s current predicament.

“I’m outraged that it’s been going on for years – years -and it’s been brought up repeatedly at different times at different meetings and the standard answer was always, ‘No, no, everything’s OK,’ Anderson said. “On Sept. 8, we had a workshop where they said, ‘There’s no fecal bacteria in Billy’s Creek – it’s from animals,’” Anderson recalled. “We were told that the Calusa Waterkeeper was wrong, but now we find out it’s the city that was wrong (and) now we’re facing a half-million-dollar-plus fine (and) whatever it’s going to cost to meet all the requirements of this decree.”

Kazemi should long ago have alerted the city to the problems, Anderson said. “We rely on our professional staff to be informed and knowledgeable in these areas and make sure we’re doing things right so we don’t have these problems.”

Kazemi did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

What galls Councilman Fred Burson is the lack of transparency.

“(Kazemi) has misled the public dramatically, and I have a real issue with that,” he said. “I was never informed of DEP fines or anything of that nature. I’m only finding out after it’s posted on the agenda,” he said. “When I had conversations with Saeed, he would assure me everything was fine, that Cassani is not accurate. He never told me about all the negotiations with DEP. Now all of a sudden we realize he was being less than truthful with me and the council in general,” Burson said.

Anderson particularly resents the time and energy this will require being diverted from other pressing matters: Homelessness, affordable housing and building unity. “Well, now, my attention is diverted away from these to focus on this issue,” he said. “That shouldn’t have happened.”

Going Forward

So what’s next?The draft consent order gives the city 60 days to define its in-kind services proposal, said city spokeswoman Stephanie Schaffer, who points out the order commits the city to carry out projects already included in the city’s 10-year capital improvement program budget.

Such projects are never-ending, Henderson said. “In my time on council and as mayor hundreds of millions have been spent on infrastructure and long-term capital improvements. This will go on for all eternity.”

Anderson and Burson want to convene public meetings and begin taking action right away. Burson intends to include Calusa Waterkeeper this time.

“I’m going to stay after (Kazemi) on this and whoever becomes city manager, and I’m going to work with John Cassani on real solutions.”

For his part, Cassani hopes the penalties and mandated improvements lead to solid changes that aren’t just a temporary patch. Old, unmaintained sewage infrastructure is a statewide problem that will take more funding and political will to fix, he said.

“I hope we’re moving forward to get some of these problems addressed, finally.”

Continue Reading