Originally published in the News-Press by Amy Bennett Williams on December 29, 2025

For years, Manuel’s Branch has failed Florida’s most basic test for public waterways: that they be safe for people to touch.

There’s too much human poop in the creek, which flows though the narrow urban creek, which winds through McGregor Boulevard backyards, past Lee Memorial Hospital, Fort Myers High ballfields and a neighborhood park.

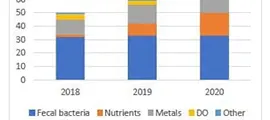

Manuel’s Branch’s fecal bacteria levels regularly test far above state safety standards according to both government data and independent testing.

The problem is not new.

City monitoring from 2016 through 2021 showed more than 90% of samples exceeded allowable limits of E. coli, a fecal bacterium used to signal contamination from human or animal waste. More recent data show little improvement. In some locations, levels routinely surpass the state’s “no-swim” threshold even when the system’s not overloaded with stormwater.

Now, a multi-year investigation by the nonprofit Calusa Waterkeeper implicates human sewage – and suggests that the city’s search for where it’s coming from stopped too soon.

The nonprofit presented its findings in December to Fort Myers’ Environmental Advisory Board. At the meeting, Waterkeeper volunteer Ken Chernesky and board member Jason Pim broke down years of testing and statistics while repeatedly offering their nonprofit’s guidance.

Board members listened and asked questions but stopped short of taking action.

When The News-Press later requested a follow-up interview and a water-quality overview, city spokeswoman Noelle Casagrande declined, writing in an email that the city would address the issue at the board’s January meeting. Until then, “We’re directing any media to attend that to learn more, including the topics you mention,” she wrote.

Manuel’s Branch fecal bacteria at: ‘a very concerning level’

As Waterkeeper’s Chernesky told the board, the creek has for years exceeded the safe level “by orders of magnitude” – and it’s not just the nonprofit’s numbers revealing this, Chernesky pointed out. The city’s own data show the same problem.

Waterkeeper’s late December testing numbers underline the problem. All points sampled in the creek returned “extremely poor” results, with one spot showing 17,239 enteric bacteria per milliliter, a number the state Department of Environmental Protection calls a “very concerning level (that) should grab the attention of restoration coordinators.”

Calusa Waterkeeper’s focus on Manuel’s Branch reflects both urgency and opportunity, said Pim.“In general, we track a long list of water quality issues affecting our work area,” Pim wrote in a follow-up email. He acknowledged that “the lion’s share of nutrient pollution ailing the Caloosahatchee watershed is from agricultural lands upstream of our coastal population centers,” which largely must be addressed by the state of Florida.

That reality, he said, makes it especially important for coastal communities to address pollution sources within their own control. “How can we ask our neighbors upstream to change their ways, if we can’t be more responsible for the impact our fertilizer, wastewater and other stormwater pollutants have on the environment?”

Waterkeeper volunteers test more than 30 sites each month for fecal indicator bacteria, focusing on places where the public is most likely to come into contact with the water: public parks, boat ramps and paddlecraft launches.

“These are areas where people often interact with the water, but the Florida Department of Health is not required to test,” Pim said. The state’s Healthy Beaches program monitors coastal shorelines, but not freshwater sites, even when people wade or play in them.

Over time, the nonprofit’s monitoring has repeatedly pointed to the same chronic trouble zones. (There’s no question that human poop is a key source of the pollution – not simply birds or other animals as the city has suggested in the past. How do we know? Birds don’t use Splenda, a Sucralose-based artificial sweetener. When samples turn up with Sucralose, it’s a sure sign the contamination in question came from people.)

“Our most frequent hotspots that greatly exceed state standards have been in Billy’s Creek and Manuel’s Branch in Fort Myers,” Pim said.

Manuel’s Branch: Picturesque and historic, but dogged with pollution

The creek’s troubles are nothing new.

In 2017, its waters ran red after a hospital contractor dumped diagnostic dye into a drain feeding the creek. In 2020, Manuel’s Branch was the site of the largest raw sewage spill in Fort Myers history, when roughly 180,000 gallons flowed through backyards near the Edison Home.

Those events plus others got the city slapped with a consent order by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection in 2020.

The agency said the city had “not addressed (flows) of untreated human waste, which poses a risk to human health.” In 2021, the two signed a consent agreement requiring $768,000 in fixes instead of a $500,000 fine and the promise to remedy things by 2028. After hurricanes, a swelling population and changes in the economy, the city renegotiated the terms of the agreement with the state in early 2025.

That revised agreement extends the deadline until 2032 to eliminate 99% of the 13.89 million gallons of treated wastewater the city discharges into the Caloosahatchee daily.

Part of the original order included testing to see whether the bacteria came from human sources or not. The city did that testing, then stopped after two tests didn’t show human origin.

“Our primary disappointment though is that they are considered to be in compliance with the human source tracing aspects … which allowed the city to stop that monitoring and reporting in summer/fall of 2024.”

But just improving capacity in the city’s big treatment plants won’t fix the creeks, where the pollution is localized – likely from old, broken plumbing and illegal creek dumping.

The ongoing poor results speak for themselves, says volunteer Manuel’s Branch water sampler Don Lees. “We have a history now that shows the quality of the water – regardless of what the city or the Department of Environmental Protection comes up with, I can tell you that I don’t see the improvements,” he said after a morning spent dipping a sampling pole into the creek. “If the end results show that we aren’t getting significant improvement in water quality, then there’s something wrong with the system (and) we have an objective record.”

‘One of the hottest spots we’ve found in our work area’

Why is the group focusing on Manuel’s Branch? “It’s not that we want to pick on the City of Fort Myers,” Pim said, “It’s that it’s one of the hottest spots we’ve found in our work area over the last six, seven years and it has that recreational contact risk.”

Plus, it’s relatively small and entirely within city limits, so would make an excellent restoration case study – one that could be applied to similarly compromised waterbodies as Florida urbanizes, he said.His organization stands ready to work with city and state officials to identify those sources and reduce ongoing public health risks, and hopes Manuel’s Branch can become not just a warning sign, but a model for restoration.

“If we can find new tools, we feel it could be a really important pilot,” Pim said, “both in our work area and throughout Florida.”

Attend or watch the next Environmental Advisory Board meeting

Manuel’s Branch will be discussed at next meeting, 12:30 p.m. Jan. 6 in City Council chambers, 2200 Second St., Fort Myers, 239-321-7000. Past meetings are online: https://vimeo.com/fortmyers

Original Story