Treasure Coast lawmakers admit Florida’s flagship program to reduce water pollution isn’t working. But none are taking action during this legislative session to change it.

The Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) has legally enforceable strategies for landowners to reduce pollution, but Florida isn’t enforcing them beyond warning letters.

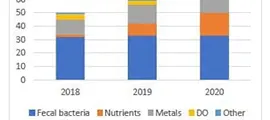

A TCPalm investigation posted Jan. 5 proves all basins around Lake Okeechobee with available data exceeded state phosphorus pollution limits over a five-year average.

Lawmakers have suggested more money for the Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services to inspect farms every two years as required, to ensure farmers are complying with pollution-reduction rules, called Best Management Practices (BMP).

However, no legislative bills seek that funding nor enforcement for noncompliant farms in drainage basins that have exceeded state pollution limits, despite the Agriculture Departmen having inspected 80% of them, according to agency spokeswoman Erin Moffet.

No bills address key problems with BMP or BMAP, either. They don’t require fines or legal action against noncompliant landowners; nor more water quality monitors to pinpoint individual polluters; nor more fertilizer reduction measures.

In fact, one bill could allow more fertilizer use, which can spark red tides and toxic algae blooms in Lake O and the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee rivers. Algal blooms kill seagrasses, which are manatees’ main food source, causing a record die-off in 2021.

The Treasure Coast’s congressman said he doesn’t think more money is the answer, and he questioned why the state has not recognized the truth TCPalm exposed.

“The two of you (reporters) … put together some pretty convincing arguments and looked at the numbers pretty convincingly,” U.S. Rep. Brian Mast, RPalm City, said. “They’re not hitting the numbers. … [Florida] came up with a program that is not getting the job done.”

Two state lawmakers acknowledged BMAP isn’t working, but five wouldn’t answer TCPalm’s questions about the problems and possible solutions: Sens. Gayle Harrell and Debbie Mayfield, and Reps. Erin Grall, Dana Trabulsy and Kaylee Tuck, all Republicans.

Rep. Toby Overdorf of Palm City, a biologist and environmental consultant, told voters while campaigning in 2018 that more environmental regulations could help waterways. Today, voters would be “correct that I haven’t done enough,” he told TCPalm this month.

“It is a long-term process that unfortunately is long-term. I want to have it done yesterday,” he said. “Your readers are right to say there needs to be a lot more done because there is a lot more to do.”

More inspectors, more data to pinpoint polluters, more water quality training and education for smaller farms could help, he said. But he didn’t commit to any policy changes, and said he’s only one of 120 House members.

“So if it’s me, and there’s 119 on the other side, unfortunately that legislation is not going to get passed,” he said. “I’m not the governor. I’m not somebody that has a tremendous amount of power.”

Gov. Ron DeSantis declined TCPalm’s interview requests before and after its investigation, and his spokesperson’s prepared statement didn’t answer questions.

GOP Rep. John Snyder of Stuart said BMAP is too complex to blame one person or agency, and there’s no “silver bullet” to fix it. He also didn’t commit to any specific solutions.

“I want to look at myself in the mirror and say, ‘What can I do in my role and in my lane?’ ” he said. “I’m in this seat and so the accountability falls on me to do the best I can in the short amount of time that I’ll be here. I feel that pressure to try and maximize every moment.”

Florida is a “law and order state” where farmers shouldn’t be exempt from rules, he said. But he wouldn’t comment on known polluters such as Rio Rancho, the sole landowner in basin S-154C, which exceeded state pollution limits by 19 times, without penalties.

While no bills crack down on pollution, one could even exacerbate it.

Instead of curbing fertilizer use, Senate Bill 1000, which lawmakers advanced to its next committee hearing Jan. 10, would allow farmers to tailor applications based on “market conditions” and other factors, including hired professionals’ recommendations.

The bill also retains the honor system that presumes farmers are complying with state rules, which sparked broad opposition from Agriculture Department leaders and multiple nonprofit environmental organizations across the state.

“We are concerned that some of the provisions in (the bill) would erode the progress made over the past three years,” Agriculture Commissioner Nikki Fried, a Democrat running for governor this year, said in a prepared statement to TCPalm.

Friends of the Everglades opposes the bill in its legislative preview.

“The ‘presumption of compliance’ with clean-water rules mustn’t be expanded, but reined in,” according to the Stuart-based nonprofit.

Fried said the “best path forward” to improve water quality and help farmers be more efficient is Senate Bill 904, filed by Democrat Gary Farmer of Broward County.

Yet that bill still doesn’t address root problems. While it would require — instead of simply authorize — the Agriculture Department to craft and implement rules to reduce pollution, it doesn’t ensure stricter enforcement and penalties.

“I wouldn’t say it’s landmark,” said Overdorf, a Republican, citing similarities to the 2020 Clean Waterways Act. “It’s fairly inconsequential. It doesn’t do a whole heck of a lot to improve water quality. Unfortunately, I feel like this is an election-year partisan move.”

Most of the land around Lake O is agricultural, so farmers bear most of the responsibility for polluting it, TCPalm’s investigation shows.

The Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) estimates as much as 78% of the phosphorus flowing into the Lake O watershed is from agriculture. Among the 1.6 million acres of agricultural land around Lake O as of December 2019, 13% were not enrolled in BMP as required as of July 2021.

But lawmakers were hesitant to focus on farmers over lesser culprits, such as septic tanks and wastewater treatment plants. They also didn’t blame DEP and the Agriculture Department for pointing fingers about which agency is responsible for enforcing BMP and BMAP.

If anything, the Legislature and political influences are to blame and the finger-pointing “is coming from the top,” Overdorf said.

“If you get down in the weeds and you talk to the people who are actually doing the work, there is no finger-pointing,” he said of DEP and Agriculture Department staff. “They’re trying to work as much as they can together and as much as they can to solve the problem.”

The DEP declined to answer TCPalm’s questions about BMAP’s lack of enforcement. Fried acknowledged the Agriculture Department needs to crack down and is now gathering data to do so.

Regardless of who’s to blame, the bottom line is neither agency is enforcing the rules.

“Clearly, there’s an issue going on with the left hand and right hand between these two different agencies,” Mast said.

View Story at TCPalm.com