Something needs to be done about the Chiquita Lock. The lock was designed to prevent Cape Coral’s polluted water from entering the Caloosahatchee estuary. It has fallen into disrepair, is a headache for boaters, and is dangerous for manatees.

Since Hurricane Ian, the lock has been broken open, allowing pollutants to flow freely into the Caloosahatchee estuary. While the city wants to remove the lock, we should not throw the baby out with the bathwater. Instead, the lock should be updated so it can continue to protect the Caloosahatchee estuary without impacting manatees and boaters.

The Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation’s (SCCF) mission is to protect and care for Southwest Florida’s coastal ecosystems. Inherent in a healthy ecosystem is clean water, which is unfortunately becoming a scarce resource. Nutrients from stormwater and wastewater feed massive algal blooms in our marine environments.

The Chiquita Lock was installed after a consent order was issued that required the implementation and maintenance of a spreader system to prevent polluted stormwater from harming the Caloosahatchee estuary.

The lock serves as a barrier, raising the water level in the canals until it spills over the southern edge and is naturally filtered through 3,000 feet of mangroves before entering the estuary. Even broken open in its current state it is still functioning at a limited capacity.

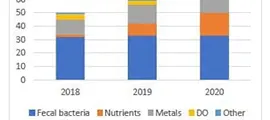

The need for the lock has not gone away. The waters within Cape Coral’s canals are still polluted, and if they are allowed to flow freely into the estuary, our environment will suffer. The consent order requires the City of Cape Coral to maintain the lock, but it has failed to do so.

The lock has proven to be a nuisance for boaters and it has been fatal to manatees, like many of the locks around Florida. While this is horrific and must be avoided at all costs, removing the lock will cause greater devastation.

Additional pollution in the estuary will impact already depleted seagrass beds, which are a major food source for manatees. While 19 manatees were killed in boat lifts across Florida in 2022, another 800 died of starvation. Protecting manatees requires protecting seagrass, which means preserving the Chiquita Lock.

It is clear that changes need to be made to the lock. Instead of removing it, we have an opportunity to fix it so it functions for the benefit of everybody — boaters, manatees, and the environment. A high-speed, two-way lock could be installed that would drastically cut down wait times for boaters. A combination of sensors, manatee exclusion devices, and a lock tender could ensure that manatees are not unwittingly caught in the lock.

The Chiquita Lock is a headache for boaters and Cape Coral, and while its removal would have small benefits, the environmental consequences would be devastating. Instead, the city should uphold its responsibility to ensure that the spreader system continues to function by fixing the lock and updating it to serve the needs of all stakeholders, boaters, manatees, and all of Southwest Florida’s coastal ecosystems.

Read our Position Paper

Read on News-Press.com