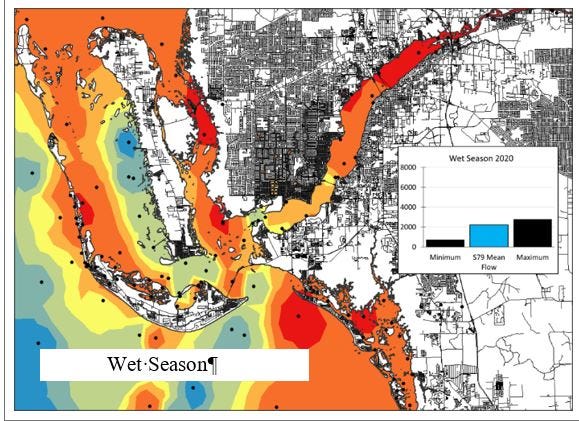

From Charlotte Harbor south to San Carlos Bay, a draft state report shows widespread pollution from the fertilizer nitrogen and the algae byproduct, chlorophyll. Many of them also contain unhealthy levels of fecal bacteria. Even the water in the J.N. “Ding” Darling National Wildlife Refuge on Sanibel Island is tainted.

For years, the Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation has been sampling the water around its islands, and the nonprofit is now sounding the alarm, joined by other water quality advocates.

The latest report includes most of the water bodies along the Gulf of Mexico including the barrier islands and the coast – the places that power the region’s $3 billion tourism industry.

It’s an industry still traumatized by 2018’s devastating dual toxic blooms of red tide and cyanobacteria. The microorganisms responsible for both can be fed by nutrient pollution.

“Our water’s still beautiful. Just because the water bodies are impaired doesn’t mean they’re unsafe to be in,” he said. “It means there’s an imbalance in the flora and fauna and nutrient levels are getting to the point where they’re starting to cause algae blooms and other impacts.”

Scientists and officials use the word “impaired” to specify exactly how water is polluted – whether from chemicals like mercury, fecal bacteria or fertilizers like phosphorus and nitrogen.

The latter two are among the most common in Southwest Florida. Though nitrogen is necessary for life, “when we get too much … it actually becomes detrimental to the natural system and harmful to the wildlife and aquatic life,” Evans said. “So we need to control what comes from human sources.” Those include residential landscapes, discharges from Lake Okeechobee, stormwater runoff and wastewater.

Disheartening as it may be, getting on the “verified impaired” list can be a first step toward freeing up the money and attention needed for restoration.

Every two years, Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection reviews water quality in the state’s 29 watershed basins to see if they meet the federal Clean Water Act’s standards.

Intended to protect the health of fish and wildlife while ensuring swimmable, fishable and, in some cases, drinkable waters, the report lists those that don’t meet the criteria.

Official designation or not, the writing has been on the wall for years, says Daniel Andrews, charter-captain-turned-water-advocate with the nonprofit Captains for Clean Water. “We’ve seen the negative impacts of discharges and nutrient pollution to Pine Island Sound for far too long,” he said. “Exacerbated algae blooms and seagrass die-offs have negative impacts on our quality of life and economy.”

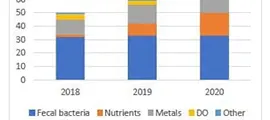

Also alarming is the clip at which polluted water bodies are increasing, says Calusa Waterkeeper John Cassani.

“The rate of impairment – particularly for nutrients – is increasing,” Cassani said. “In Lee County, the number of water bodies that are verified impaired for nutrients has increased 36% since 2018. And the other part of that is the waters with the highest level of intended protection, which the state refers to as ‘Outstanding Florida Waters,’ is one of the subsets that’s becoming more widespread impaired for nutrients.”

“What we’re seeing is a lack of data in a lot of areas, especially along the Gulf coast, where we just don’t have enough data to assess,” Evans said.

And the ones that are now listed likely have been tainted for a while, he said. “These water bodies could have been impaired a long time – it’s just that we’re now getting enough data to show that they’re truly impaired and move them to the “verified impaired” list because finally, we have enough data to demonstrate they were impaired.”

To blame: Florida’s rocketing population growth, Evans said. “With 1,000 people a day moving to the state of Florida, that’s putting a lot of pressure on these natural systems and their ability to filter and clean our water … So the loss of wetlands combined with the amount of development … that’s why we’re seeing these waterbodies become impaired.”

Next, the state figures out where the excess is coming from and works with stakeholders like communities or farms to reduce that. It develops what’s called a basin management action plan to “reduce those loads, develop a list of projects and show progress to DEP that we’re trying to meet those load allocations,” Evans said.

That’s in theory, at least. How things work in practice is another story. Even once a plan is in force, improvements may not happen.

For example, Evans said, some years ago, there was a nitrogen goal for the tidal basin of the Caloosahatchee intended to reduce that nitrogen load by 23%. Even so, “we continued to watch those nutrient levels increasing,” he said.

Farther south, the action plans for two Estero Bay tributaries, south Fort Myers’ Hendry Creek and Bonita Springs’ Imperial River haven’t helped, says Estero resident Ed Shinouskis, a volunteer Calusa Waterkeeper ranger.

“We have definitive proof that at least these two BMAPs are not working, even though over $56 million has been spent so far,” Shinouskis wrote in an email. Despite 39 projects to reduce their total nitrogen load from 2014 to 2020, levels in both water bodies have only increased, he said.

And, Cassani points out, the time between identification and improvement can lag. Neither Matlacha Pass Aquatic Preserve nor Estero Bay, placed on the list in 2015 and 2019 respectively, have had their total maximum daily load determined. “We’re just not seeing TMDLs keep pace with the rate of impairment, especially for nutrients and fecal bacteria,” Cassani said.

Evans agrees. “When you look at the recent history, I’d say our record isn’t fantastic,” Evans said. “When you look at it from the larger watershed perspective in Lee County, I think the jury’s still out (but) we need to make sure they are working because we’re spending millions in taxpayer dollars.”

There are bright spots, including fertilizer ordinances in Lee County, Cape Coral and Sanibel, which also has created several effective filter marshes, while conserving much of its wildland. “On Sanibel, we’ve been able to preserve over two-thirds of the island in conservation and the majority of those are wetlands, which are nature’s filter,” Evans said.

Yet even with all the things Sanibel and Captiva have done to improve water quality, “the end result is we’re still continuing to see waterbodies become impaired,” he said. “That doesn’t mean that what we’re doing isn’t helping, because it is.” But until the mainland follows the islands’ lead, success will be limited.

“We need to see better protection of wetlands throughout the Caloosahatchee watershed if we’re going to see improvements in water quality and we need to restore wetlands, or else we’re going to continue to see declines in water quality.”

That’s where engaged citizens and business owners come in, he and Andrews say.

“It’s critical that people who use our water resources, who make a living on our resources, who live along our resources know these water bodies are impaired so they can take actions on their own,” Evans said. Curbing fertilizer use, treating stormwater and reducing runoff from farm fields all have a direct impact, he said.

And it behooves communities to take action, Andrews says, lest the barren seagrass prairies and dead oyster bars he’s increasingly seen in recent years disappear entirely. “Time is running out to fix these problems before we hit a tipping point.”

Read Story from News-Press.com