Many residents may recall how the Matlacha bridge used to be known as the “fishingest bridge” in the USA. The bridge would be crowded with fisher folk at night. Drive over the bridge today and how many people do you see fishing?

The Cape’s pretense is that the Chiquita Lock constitutes a safety hazard to boaters. Removing the lock is a really bad idea. Some believe the city seeks to raise property values by creating quicker boat access to the Caloosahatchee. Raising property values means the Cape will collect more taxes. Most of the residents west of Chiquita Boulevard do not have a boat and they may end up paying higher taxes just to facilitate those who do.

The Cape left the lock open — intentionally during Hurricane Irma. The storm moved so much water out of the river toward the coast that the canal water levels declined and likely contributed to the rash of seawalls collapsing within the system. Will waterfront property owners or Cape taxpayers or both pay for this repair? What happens next time a hurricane strikes the Cape if the lock is removed?

A court order mandated the Chiquita lock so as to contain about 800 acres of brackish canals referred to as a spreader system in the southwestern part of the city. Florida specified this action in response to damage done to the coastal resources by the Cape’s initial developer, the Gulf American Corporation.

The spreader canal configuration cleans polluted water flowing downstream into the spreader from the city’s freshwater canal system. When the lock functions as intended, it holds the polluted water and eventually spreads it out into the mangrove fringe where nature does the cleaning.

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) cannot issue a permit to remove the lock if this will cause or contribute to the impairment of a downstream water body. If the Cape can demonstrate mitigation that compensates for the “causing or contributing,” then DEP may issue the permit.

The Cape now makes the bizarre argument that the freshwater canal system affords mitigation, allowing for the lock’s removal. This is the same freshwater canal system that constitutes the source of the runoff problem that required the need for the spreader system and lock some 40-50 years ago.

After years of legacy pollutant loading, the canals will add more pollution — not reduce it. The Cape needs to do a nutrient budget study to settle this issue, but so far has failed to undertake such a study.

Without the lock, the City’s polluted runoff will seek the source of least resistance. This happened when the Ceitus Boat Lift was removed in northwest Cape Coral where more than 70 percent of the runoff now enters Matlacha Pass at one location rather than spread over a mangrove forest to diminish the impact and increase the cleansing effect.

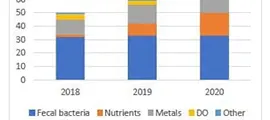

Matlacha Pass was verified as impaired for nutrient pollution in 2015, after the Ceitus lift removal in 2008.

Without the lock, massive pulses of polluted freshwater and increased boat traffic will enter the Caloosahatchee Estuary in close proximity to an endangered smalltooth sawfish critical habitat area. The Caloosahatchee is one of the few remaining habitats left where this species still remains.

Please help protect Cape property owners and fish by contacting the Cape Coral mayor and city council and ask that the application to remove the Chiquita Lock be withdrawn.