Originally published in the News-Press by Amy Bennett Williams on February 18, 2026

The algae stretches for miles along the Caloosahatchee: clouding the shoreline, murking up canals and choking oxbows, a dull avocado taint that signals nothing good.

Despite a health department all-clear of an Alva canal, the 45-mile-long big picture from Lake Okeechobee to the W.P. Franklin Lock and Dam in Lee County is quite different.

Pilot Ralph Arwood flew the river Feb. 14 and photographed mile after mile of the mess.

Though a big dry-season bloom is much less common that one when it rains, the drought itself may be to blame, says Professor of Marine Science Mike Parsons at Florida Gulf Coast University’s Water School.

Parsons thinks the drought-created stagnant water is the likely culprit. “Blue-green algae tends to prefer ‘aged water’ that has been sitting around for a while,” he wrote in an email, “We’re still not sure why they benefit from that (million dollar question), but it’s pretty consistent. As the waters warm, the cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) will have higher metabolic rates which may lead to more growth and a bloom.”

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection did not respond to repeated questions about whether it has sampled the bloom to determine the species and whether it is producing toxins.

However, FGCU algae expert Barry Rosen recently traveled to Alva to do just that.

He came up with Microcystis flos-aquae, a member of a genus that produces toxins that can cause liver damage, form tumors and have been linked to grave neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and ALS.

“The question really is: Is this particular organism transient,” he asks. “Obviously it has the right nutrients, the right light intensity and the temperature’s right … what’s next? Will there be something else waiting in the wings to take over? Will this one peter out?” he asks.

But those are questions for the future, Rosen says.

For now. “There’s not enough flow to dislodge it at this point. If it’s getting into backwaters and canals, it could continue to grow. There’s nothing preventing that until something that it needs runs out.”

At the moment, “We’re in the sweet spot that allows this organism to proliferate.”

Does Rosen presume the algae he found in Alva is the same stuff blooming 35 miles up river near Moore Haven? “Yes,” he said. “I wouldn’t doubt it’s the same organism.”

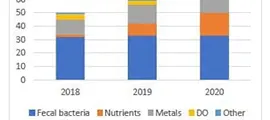

As for the “why?” of the bloom, Calusa Waterkeeper board member Jason Pim wants to focus on the source. “We could speculate and debate about the specific weather and water management conditions that have led to this bloom, but the most important factor is that there continues to be more than enough nitrogen and phosphorus pollution in our waters to support harmful algal blooms.”

Bottom line: “The state must do more to stop nutrient pollution before it enters the water. Trying to address it after the fact takes exponentially more effort and (taxpayer) money,” Pim said.

One small potential bright spot, Pim says: “Due to current drought and the lowest Lake O level in recent memory, the estuary is much higher in salinity and thus any bloom would not be expected to survive long after being discharged beyond the Franklin Locks.”

Then again, that’s a problem too, because “We want much more freshwater and less salinity in order to stop the collapse of tapegrass in the upper estuary.” “

Unfortunately, Pim says, “The C-43 Reservoir – intended to give us more flexibility in situations like this –sits empty, despite the ribbon cutting last July.”

Original Story