If you’ve ever watched young children at the beach making sandcastles while fighting against occasional waves breaking over their hard-won efforts, you can appreciate the futility of beach nourishments. Although a necessary part of coastal living in Florida, the benefits of periodic nourishments to your home beach come with a slurry of environmental impacts that are oftentimes overlooked and downplayed. Currently we have no alternatives to periodic nourishments to restore beaches affected by natural erosion and storm damage, both exacerbated by changing climate indicators. A recent nourishment on Fort Myers Beach (FMB) garnered lots of attention throughout 2025, but to evaluate that nourishment we need to first go over some basics.

As population increases have driven coastal development to the tune of 2.7+ million people over each of the last 5 decades in Florida, pressure to maintain beaches for recreation has increased tremendously. The intensity of tropical storms/hurricanes especially over the past several years (Hurricanes Irma, Ian, Helene, Milton) highlighted the vulnerability of our Gulf Coast beaches and the enormity of the costs to restore those affected beaches. Of course, humans are Johnny-come-latelies to our beaches, while sea turtles, shorebirds and a host of other animals rely on those same beaches for their survival as well!

Breaking it Down

The nuts and bolts of how beach nourishments work are important in understanding both the benefits and negative impacts that result. Whether from natural erosion or storm-induced sand loss, our south Florida beaches are changing dramatically. By altering much of the natural sand accretion from riverine sands/estuaries resulting from development and shoreline armoring, we have lost historically important natural beach restoration sand sources. Naturally, beaches, especially barrier beaches are ephemeral, changing their conformation from year to year. The problem is we have developed these shorelines right up to the beach uplands making us vulnerable to increasingly fierce storm surge and rising sea levels.

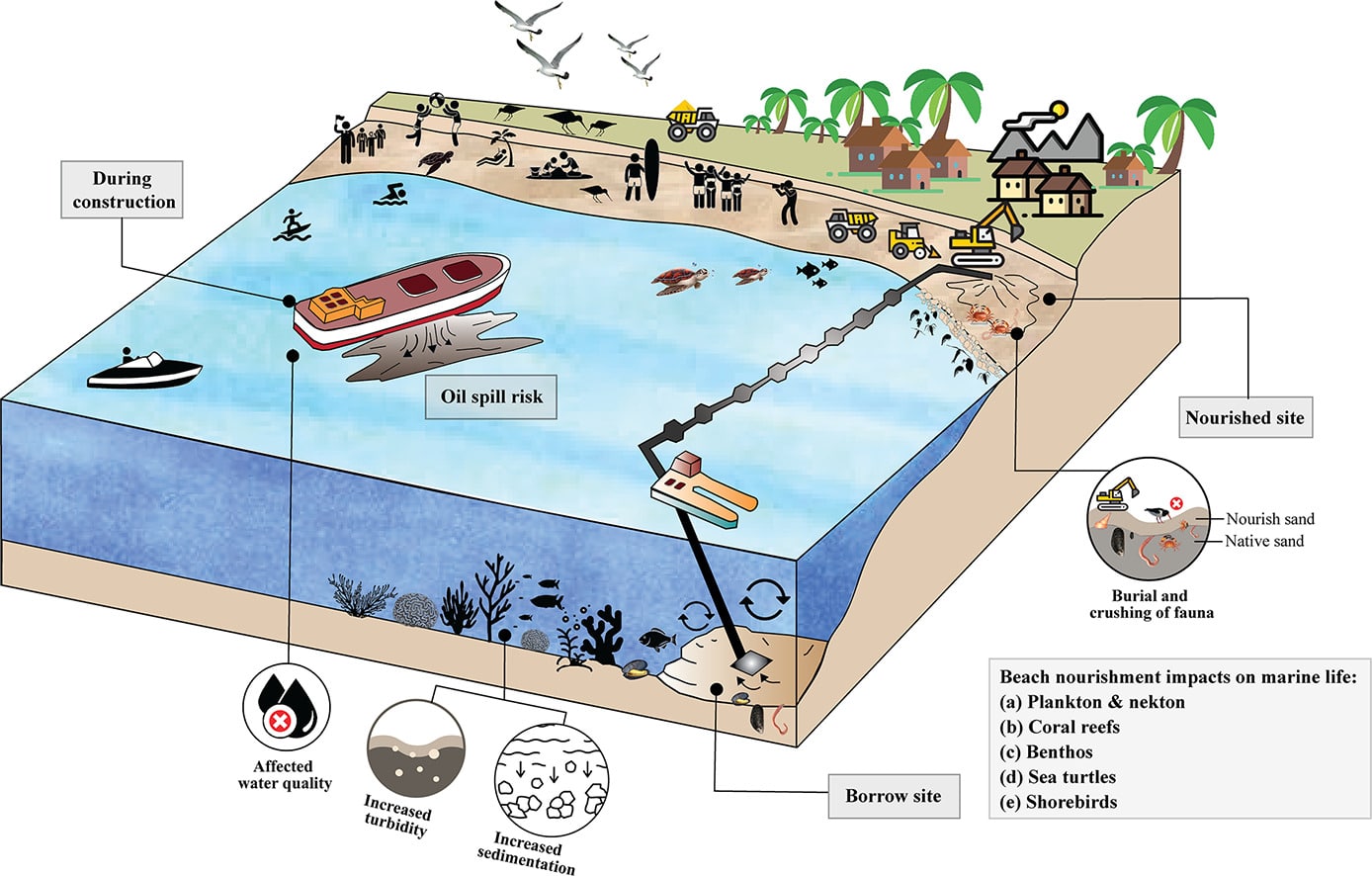

There are multiple direct and indirect adverse effects that result from beach nourishments and you can frame these impacts over areas: 1) the BORROW site where sand is excavated from and; 2) the NOURISHMENT site (beach and surf zone) where the sand is placed. There are adverse effects from hopper/cutterhead dredging to supply sand; pipelines threaded underwater and up onto the beach (blocking nesting sea turtles/hatchlings), sand source quality for sea turtle and shorebird nesting, equipment lighting (nesting sea turtles/hatchlings). Let’s briefly discuss these routes of effects.

Impacts from Beach Nourishments using Offshore Sand. Source: Jeopardizing the environment with beach nourishment. Science of the Total Environment, Volume 868, 10 April 2023.

At the Borrow Site(s)

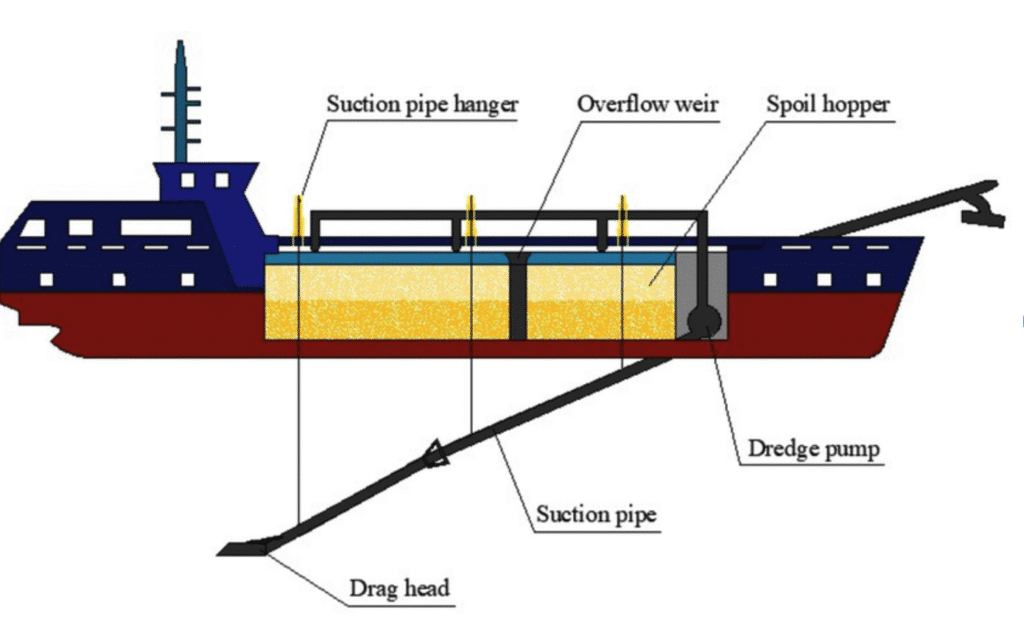

Most of the Gulf Coast beach nourishments utilize offshore borrow pits requiring hopper dredges for sand extraction. A suitable sand source is chosen nearby if available sources have not been tapped out. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) reviews these sites for state waters, and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) performs reviews for federal offshore waters. Hopper dredges then suction dredge with large drag heads across the sea floor and suck in tons of sand (e.g., over 1 million cubic yards of sand along 6.5 mi for the FMB nourishment).

Dredging removes benthic habitat that is an important part of the ecosystem even if there is no submerged aquatic vegetation in the borrow area. The sediment may look to the uninformed eyes to be just sand and muck, but this is home to a diverse marine invertebrate community (e.g., shrimp, crabs, snails, lobsters, sponges) and juvenile fishes. Dredging first destroys the three-dimensional structure of the benthic habitat, somewhat analogous to clear-cutting a forest. Important habitat is removed and takes significant time to recover; not as simple as sand filling in from adjacent areas outside the dredge footprint over a few months, for instance.

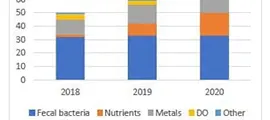

The bacterial community is also deeply affected by dredging in that any rooted vegetation, microalgae, and biofilms consisting of associations between microalgae and bacteria are disturbed. Toxic algal blooms can result from the dredged area perturbation. Trapped nutrients in the sediment are released with dredging such as nitrogen, phosphorous, organic carbon, contaminant and toxic substances. As sediment is suspended, surf zone concentrations of fecal indicator bacteria typically increase.

Dredging also causes significant turbidity in the water at the dredged borrow site and in the surf zone from sand placement and tidal washing impacts phytoplankton, zooplankton and nekton (shrimp, fish, crustaceans). You might assume that the benthic area is ephemeral and that tides and tropical storms cause turbulence naturally. However, borrow sites are typically offshore in somewhat deeper waters that the benthic community rarely gets disturbed beyond the surface layer and these areas have time to build complex, biologically diverse community structure. Aside from all the suspended solids in the water, turbulence affects fish and other species ability to forage and escape predators. Turbulence caused by dredging is often continuous (24/7), not allowing for suspended solids to fully settle during operations. Sand placement is the second source of turbidity. The tidal washing resuspends significant amounts of sand back into the surf zone and beyond. This causes not only environmental impacts but makes beachgoing unpalatable during active nourishments and water quality perhaps unsafe for swimming.

July – October, 2025

Hopper dredge and barge operations in the Gulf off Fort Myers Beach and Sanibel during the recent Fort Myers Beach (Estero Island) nourishment. You can see the dredged area clearly. Photo Credits: Ralph Arwood.

At the Nourishment Site

Sand placement also carries a significant impact related to the quality of the replacement sand compared with what was lost as well as the final slope of the nourished beach and the amount of compaction. Looking at sand quality just from the perspective of nesting sea turtles and hatchling development and survival, replacement sand can make a huge difference. Nesting females returning to their native beaches to nest seek compatible sand that they can excavate for suitable nest chambers to oviposit their eggs.

Sand sourcing can impact the integrity of nest chambers (how well they maintain their structure given the time needed for hatchlings to emerge, (e.g., 45-60 days for loggerheads in the Gulf) preventing chamber collapse. Grain size and composition of sand can even determine the success rate of emergent hatchlings to erupt from their nesting chambers. Too soft and fine in texture and hatchlings may not be able to erupt from the chamber. Temperature and humidity within the chamber are also affected by the suitability of the replacement sand and that can be a determinant in survivability and the sex ratio of emergent hatchlings. Sand quality can even affect the susceptibility of eggs/hatchlings to being dug up by predators (e.g., coyotes, racoons, bobcats, domestic dogs) and the absence/presence of in-chamber predators like crabs and invasive fire ants.

July – August 2025

Suspended sand in the mixing zone at FMB during nourishment. Photo Credits: Ralph Arwood.

Lethal Practices

Hopper dredging comes at a high cost, killing many sea turtles in the Gulf. Those deaths or “takes” as they are legally termed under the Endangered Species Act, are covered for most projects under a cooperative programmatic biological opinion between the USACE and National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). The Gulf Regional Biological Opinion (GRBO) operates for hopper and cutterhead dredging in state waters within the Gulf of Mexico. While operating safely, hopper dredges utilize drag heads that are only operational while the drag head is suctioning sediment along the bottom as the dredge is moving.

However, when the drag head is lifted off the bottom and is still suctioning, there is considerable risk that sea turtles in the area could get impinged in the drag head. Operationally, the suction is supposed to be off when the drag head is lifted off the water bottom but when an operator tries to clean out the suction lines, they may keep the suction running while the drag head is in the water column, in violation of operating procedure typically, increasing the risk of turtles being suctioned through the drag head into the hopper along with all the sediment, always lethal. Relocation trawling may be required in areas anticipated to have a lot of sea turtles (seasonally off nesting beaches, for instance) and can mitigate the risk to sea turtles in addition to using drag head deflectors.

Hopper Dredge illustrating the suction pipe attached to the drag head where sea turtles and other species can be sucked into the hopper.

Other impacts from nourishment projects include extending dredge pipelines for weeks/months during sea turtle nesting season onto the beach (e.g., Fort Myers Beach). When nesting sea turtles encounter the pipeline, they turn back to the Gulf and these “false crawls” waste their energy and can lead to aborting their eggs. Staged lighting on equipment (e.g., dredges, barges, beach equipment) can disorient both nesting adults and emerging hatchlings. Inevitably, turtle patrols will miss some new nests and without relocation, those nests could be covered by sand placement, causing nest mortality. Increased vessel traffic from work vessels off a nesting beach increase the risk of vessel strikes to adult females in particular who are resting in the area before ovipositing their eggs.

Loggerhead hatchlings emerging from nest chamber on Gasparilla Island, photo courtesy Boca Grande Sea Turtle Association.

Brief Evaluation of the Fort Myers Beach Project

The final phase of the Fort Myers Beach/Estero Island nourishment was completed in late August 2025, and dune planting is ongoing this fall. The overall cost for the 2025 final phase was approximately $23 million paid out from a mix of Federal, state, county, and local sources, including FEMA, FDEP, and Lee County. The permit for the FMB nourishment resulted from an Army Corps emergency permit issued after Hurricane Ian and in cooperation with NOAA NMFS to assess potential impacts to sea turtles under the Endangered Species Act. A similar nexus involved USFWS to review potential impacts to nesting sea turtles and shorebirds (e.g., least terns, black skimmers, snowy and Wilson’s plovers). Although the nourishment was supposed to occur outside of sea turtle (May-September) and shorebird nesting seasons (beginning February), there were significant delays (7 months) due to heavy equipment (e.g., dredge) scheduling.

Ultimately measures were taken by the Town of Fort Myers Beach to mitigate the damage including sea turtle and shorebird nest relocations; however, if the nourishment was not permitted under an emergency permit (Hurricane Ian), the nourishment would have been forced to occur outside of sea turtle nesting season at least. A record number of “false crawls” for female sea turtles emerging onto the beach but returning without nesting occurred because of the dredge pipeline running parallel along the beach, blocking sea turtles from moving toward the less compacted sand up the beach.

Fort Myers Beach Pier Destroyed by Hurricane Ian (2022), slated to be rebuilt in 2026/27?

One of the pipelines used to pump dredged materials onto FMB in 2025.

Planning for the Future

Florida did have a long-term plan in the works it turns out (I know because I worked on it while at NOAA) but that plan and its Bipartisan Infrastructure Law $4.8 billion funding for Collier County alone, were indefinitely suspended 8 months ago by the current Administration. The Norfolk USACE partnered with Collier County to develop a tentatively selected plan under the Army Corps’ Coastal Storm Risk Management (CSRM) program addressing climate resilience.

Specifically, the CSRM analyzes coastal storm risks in specific areas, proposing strategies to manage those risks. Strategies include a combination of structural, non-structural, and nature-based solutions to protect coastal communities from storms and sea level changes.

Pinellas, Charlotte, Miami-Dade and other Florida counties were all slated to receive CSRM funding and developing similar long-term (50-year) coastal resilience programs, like the Collier County plan, to protect their shorelines and communities from more intense hurricanes and other climate impacts like sea level rise. Long-term planning included sophisticated/complex post-storm modeling to better inform beach nourishments in tandem with living shorelines to protect Florida coastal communities far into the future. Sadly, those projects are unlikely to move forward in the immediate future and those funds could be re-appropriated, leaving the financial and environmental burdens of increasing coastal erosion and over-development to counties, municipalities and the state.

Beach nourishment projects are proliferating around the globe because of sea level rise and ever-increasing coastal development. Environmental consequences of beach nourishments at both the borrow and nourishment sites are underestimated and not fully understood. Nourishments have finite lifespans and offer short-term solutions to an increasingly difficult problem. Close to home with the FMB nourishment recently completed, there were many unavoidable trade-offs. And since the project was delayed by 7 months to start, the nourishment overlapped with shorebird and sea turtle nesting seasons which exacerbated impacts. Currently, the regulatory process is mostly reactive to the vicissitudes of tropical storm damages and unfortunately the hold on long-term CSRM planning will keep us reactive for years to come.

What You Can Do

Be proactive and contact your elected representatives in Florida and Washington D.C. and let them know you are aware that south Florida is not getting those CSRM funds we deserve, and our current long-term coastal erosion planning will not make our coastal communities resilient and safeguard us against more intense hurricanes in the future. We can’t continue down the path of massive coastal development untethered to climate reality.

Regardless of whether our politicians recognize climate in future effective coastal erosion mitigation and costs, they need to be accountable for future nourishment planning that is affordable and sustainable. It’s important to know what we lost as Floridians when the Administration force-stopped CSRM projects. For Collier County, almost 6 years of scoping meetings and developing a tentative plan for funding went out the window in a day. Lee County had barely gotten started in the CSRM process but the plan was to follow the lead of Collier County’s tentative plan with the other Gulf coast counties.